Connecticut Construction Entrance Detail

Connecticut owes its name, and much of its identity, to the Connecticut River, a waterway that defines the state's landscape and supports nearly every aspect of life in Connecticut. Stretching 406 miles with a watershed of more than 11,000 square miles, the river accounts for roughly 70% of the freshwater flowing into Long Island Sound. Its health and purity are vital to both residents, businesses, and wildlife, and maintaining that balance is a shared responsibility among residents, communities, industries, and contractors across the state.

The river’s significance is clear across Connecticut, from historic New England towns along its valley to modern city centers like Hartford and other communities along the Connecticut River Valley. This enduring reliance on clean water means that, as Connecticut develops, the challenge of managing pollution grows. As we transition from the region’s rich history to its current environmental commitments, it becomes essential to control sediment and mud runoff, particularly from construction sites, through established protective measures. This is where Best Management Practices (BMPs), such as stabilized construction entrances, come into focus for stormwater management and environmental protection.

The Importance of Clean Water and the Connecticut River

The Connecticut River is the longest in New England and one of the most historically significant in the United States. Its extensive shoreline collects stormwater runoff from across the region and channels it toward the Sound. Because the watershed is so vast, even small sources of pollution, such as sediment tracked onto public roads from construction sites, can have significant downstream impacts.

For much of the 20th century, industrial and construction pollutants degraded water quality in the river. Sediment, oils, and heavy metals found their way into storm drains, threatening and harming the delicate ecosystems that rely on these waters. Today, the river is home to many species, including rainbow trout, pike, eels, and several mussel species, including several mussel species listed as endangered or threatened under state and federal protections.

Thanks to early water quality legislation in the 1960s and the federal Clean Water Act of 1972, the state has made measurable progress in restoring the river’s health. Most stretches are now safe for fishing, boating, and recreation, but continued vigilance is essential. Connecticut’s environmental policies focus heavily on preventing new sources of pollution by carefully managing and regulating stormwater from construction and industrial sites.

The Connecticut DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION (DEEP)

The federal Clean Water Act established the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) to regulate pollutants entering U.S. waters. In Connecticut, the NPDES program is administered by the Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP), which oversees stormwater permits and ensures compliance across construction and industrial activities.

For most contractors, the key regulation is the General Permit for the Discharge of Stormwater and Dewatering Wastewaters from Construction Activities, commonly known as the Construction Stormwater General Permit. This permit covers projects that disturb one acre or more of land, or smaller sites that are part of a larger common plan of development.

To obtain permit coverage, contractors must develop and implement a Stormwater Pollution Control Plan (SWPCP) that identifies potential pollution sources and specifies BMPs to prevent site runoff. These may include silt fences, check dams, dust control, sediment basins, and trackout control systems.

The Role of BMPs in Compliance

BMPs are not simple permit items; they are practical strategies that protect water quality and reduce liability. Without them, common pollutants such as soil, oils, cement residue, and debris escape through runoff, erosion, or vehicle movement.

DEEP’s 2002 Connecticut Guidelines for Soil Erosion and Sediment Control provide detailed direction for implementing these practices. Section 5(b) of the Construction Stormwater Guide emphasizes that an effective SWPCP should focus on minimizing pollutants before they reach the stormwater system. When applied correctly, these measures create a “closed loop” approach that captures and manages stormwater on the construction site.

Tire Tracked Soil - Construction Entrance Detail

Sediment carried onto public roads by construction vehicles, known as “trackout,” occurs when soil and mud stick to tires and are left behind as trucks exit job sites. Rain then washes this material into storm drains, which eventually flow into local rivers and the Long Island Sound.

To address this, the Construction Entrance (CE) BMP, also known as an Anti-Tracking Pad with Track-Out Mat System or Stone Stabilized Pad Construction Entrance, is installed at site access points. The CE provides a controlled surface that helps dislodge soil from vehicle tires and prevents erosion around heavily trafficked areas.

According to the 2002 Connecticut Guidelines for Soil Erosion and Sediment Control, a typical construction entrance consists of either a stone-stabilized pad or a mechanical system (such as a track-out mat, mud rack, or wheel wash) installed at the ingress/egress points. These entrances are usually among the first BMPs installed on any construction site, ensuring that equipment can access the site safely while minimizing construction site trackout from day one.

Proper placement of the Anti-Tracking Pad with track out at the system is critical; it should be located where vehicles can enter and exit the site efficiently without crossing unstable soil or drainage swales. A well-designed CE not only keeps the public roadway clean but also protects the project’s reputation and compliance record.

Stone Stabilized Pad Construction Entrance

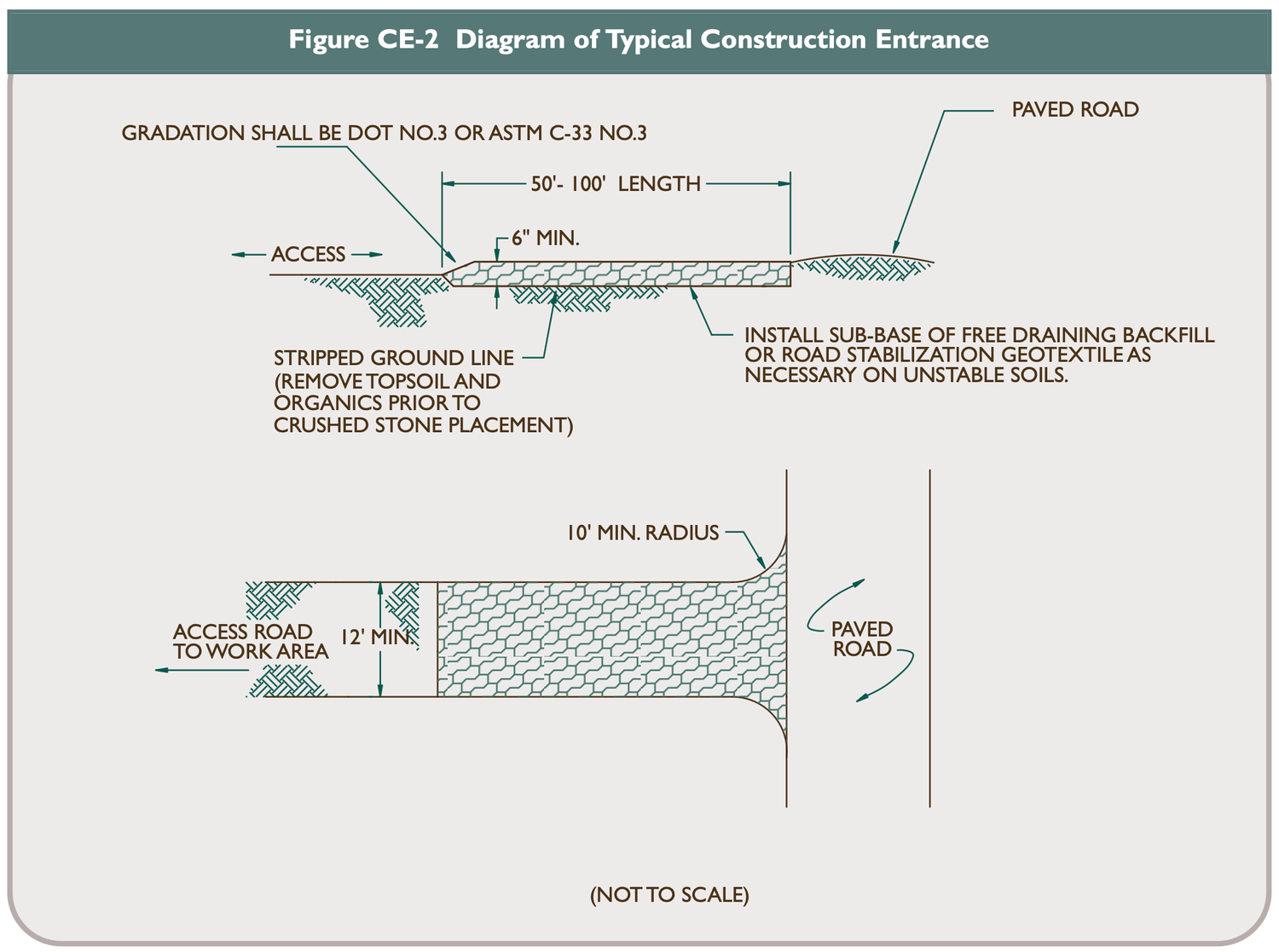

The stone-stabilized pad remains one of the most common trackout control methods used in Connecticut. It consists of a layer of coarse aggregate, typically #2 or #3 angular stone, placed over a geotextile fabric to prevent underlying soil from mixing with the aggregate. The pad is generally constructed with a minimum depth of 6 inches of clean, angular stone and a minimum width of 12 feet, or the full width of the access point. Its length typically ranges between 50 and 100 feet, depending on site conditions and anticipated traffic volume.

A geotextile layer beneath the stone separates native soil from the pad and extends the system’s service life by preventing contamination of the aggregate. Where the pad connects to a public roadway, the entrance should flare outward to accommodate truck turning movements and minimize edge degradation.

Maintenance Requirements

Over time, sediment and mud will compact within the stone layer, reducing its effectiveness and eventually turning it into a mere cobblestone road. Contractors must periodically “top dress” the pad by adding fresh aggregate. Street sweeping should also be performed regularly to prevent residual sediment from reaching storm drains.

When construction is complete, the pad must be excavated and removed before final stabilization and grading can be achieved. The excavated stone is typically disposed of as construction waste, increasing project costs through transportation requirements and landfill volume.

While common, this traditional method has proven ineffective and presents several drawbacks, including high material and disposal costs, significant labour and equipment requirements, limited flexibility for site changes or relocation, and reduced performance under high-traffic or wet conditions. These challenges have led many Connecticut contractors to explore modern, reusable alternatives, such as the FODS Track Out Mat System.

Mud Rack (Shaker Rack)

A mud rack, also known as a cattle guard or shaker rack, is a steel or reinforced frame installed at site exits to physically shake vehicles in hopes of dislodging embedded sediment from tires. The rack’s angled bars or plates create vibrations as vehicles pass over them.

The mud rack is typically placed in series in addition to a stone pad, as they have been found to be ineffective on their own. For cleaning and maintenance. Operators must remove accumulated debris from beneath the frame to prevent clogging. Mud racks are a good option for sites with heavy vehicle traffic or limited space, but they can be cumbersome to maintain over long project durations.

Wheel Wash Detail

When stone pads or mud racks do not achieve sufficient sediment removal, contractors may add a wheel wash station. These systems use pressurized water to clean tires and undercarriages before vehicles exit the site.

The wash water, which becomes sediment-laden, is then diverted to an on-site sediment basin or trap where solids can settle before discharge or recycling. Wheel wash systems can be highly effective at cleaning tires, but they also require access to a steady water supply, power, and regular maintenance to manage sediment buildup, which clogs filters.

FODS Trackout Control Mats

In Connecticut an increasingly common solution has been the use of is the FODS Anti Tracking Pad with Track Out Mat System a reusable, engineered as a complete replacement to rock pads and temporary racks.

Constructed from heavy-duty high-density polyethylene (HDPE), FODS mats feature a patented surface of raised pyramids that flex tire treads, breaking loose soil and debris while capturing it below the mat surface. Each mat measures 12 feet wide by 7 feet long in the direction of travel, allowing for modular configurations that fit any entrance layout.

Advantages of FODS in Connecticut Applications

- Superior Sediment Removal: The pyramid design cleans tires more effectively than stone pads, reducing street sweeping by 60-80%.

- Reusable and Sustainable: FODS mats can be redeployed across multiple sites for over ten years, significantly reducing material waste and cost.

- Fast Installation: A complete Anti Tracking Pad with Track Out Mat System can be installed in under 30 minutes without heavy equipment.

- Versatile Placement: Works on soil, asphalt, concrete, and even steep grades—perfect for Connecticut’s varied terrain.

- Easy Maintenance: Sediment can be brushed away using a skid-steer broom or manually with a FODS Cleanout shovel.

- Minimal Remediation: No aggregate excavation is required when the project ends, simplifying final stabilization.

These features make FODS an ideal solution for Connecticut contractors managing multiple projects, especially along the I-91 corridor, urban redevelopment sites in Hartford, and municipal infrastructure improvements statewide.

By switching from rock to FODS, operators can reduce long-term costs, improve compliance with DEEP and NPDES requirements, and demonstrate a strong commitment to sustainability.

Connecticut’s natural beauty and environmental integrity depend on the responsible management of stormwater runoff. As the state continues to modernize its infrastructure and revitalize communities, construction sites must balance productivity with environmental protection.

The construction entrance—a seemingly small component of a project—plays an outsized role in controlling sediment and safeguarding water quality. From traditional stone pads to advanced systems like FODS Trackout Control Mats, these BMPs form the first line of defense against trackout pollution.

For contractors, engineers, and environmental managers in Connecticut, adopting innovative solutions like FODS isn’t just about convenience it’s about compliance, cost efficiency, and stewardship of the waterways that define the state.